On the fires

What was lost in the Palisades Fire and how we grieve

When people ask, I say: We lost my family home in Pacific Palisades and the neighborhood I grew up in… We lost all our photos before 2008. But somehow… it rings hollow.

Because the place that my kids, my husband, and I sleep in, the home we currently rent in a different part of Los Angeles, it is still standing. My dad was living in the house that burned down, and he is staying with my sister right now until he can find a more permanent place. But I still have my king-sized bed to retreat to. I am struggling with the awareness of how lucky I am. In these weeks after the fire, the fact that I still have immense privilege is hard to hold next to the pain and grief I am trying to let myself feel.

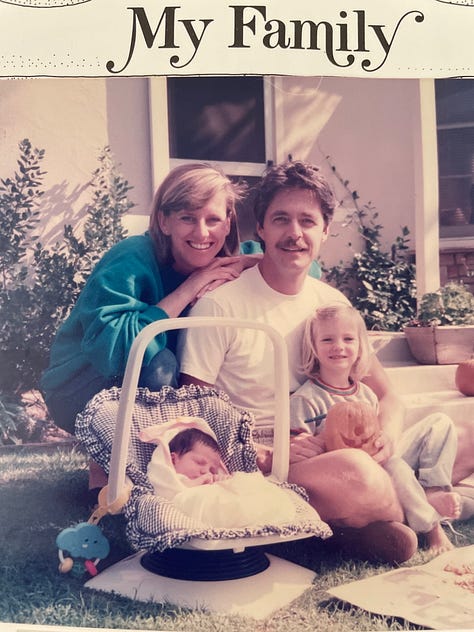

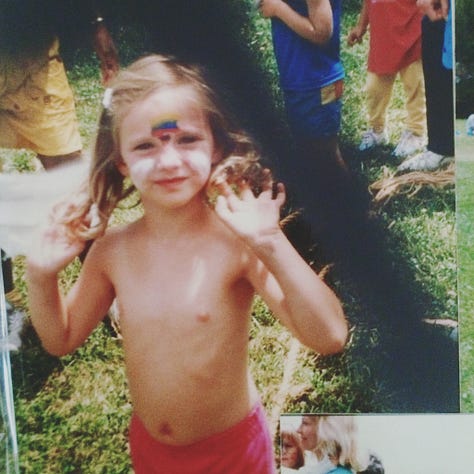

In a digital age with so much of our memories stored in the cloud, it is difficult to properly express how much was contained in the tangible items lost. How do you communicate the value of your deceased mom’s yellow cloth-covered journal from 1981 when she was pregnant with you? Or the American Girl Doll from the 90s (now retired) in a dark green Colonial Era riding gown you carefully packed away in hopes of someday having a daughter to share it with? Or the woven Kente cloth you collected when working in West Africa in your mid 20s. The Super 8 films from 1978 depicting your sunburned, baby-faced parents falling in love in a resort-free Cabo San Lucas, and the hours and hours of VHS home videos from your childhood in the 80s and 90s. Your dad’s epic CD collection with his five changer CD player. Boxes labelled “First Grade” and “Second Grade” on up to “Senior Year” that you saved. My mom, a self-proclaimed Canadian army brat, never had stuff to share with us from her childhood. I started saving those boxes 25 years before I ever had a baby of my own with the vision of someday having the time to go through them with my own kids, sharing stories that would be magically unlocked by these objects, letters, and papers.

Is it a millennial thing to continue to store precious items at your parents’ house? I have always thought that their house was the safest place in the world, a fact that reinforces my awareness of the fortuitous hand I’ve been dealt. However, due to rising housing costs and career choices, I make up a generation of native Angelinos who have yet to achieve the American dream of home ownership like our parents’ and grandparents’ generations before. So, as I moved from city to city, apartment to townhouse, always renting, my parents’ home was where I stored the stuff I never wanted to lose. Like my wedding dress, covered in panels of creamy white sequins. I wish I could hold it once more and feel its weight, like the weight of the hug from my mother I will never again receive.

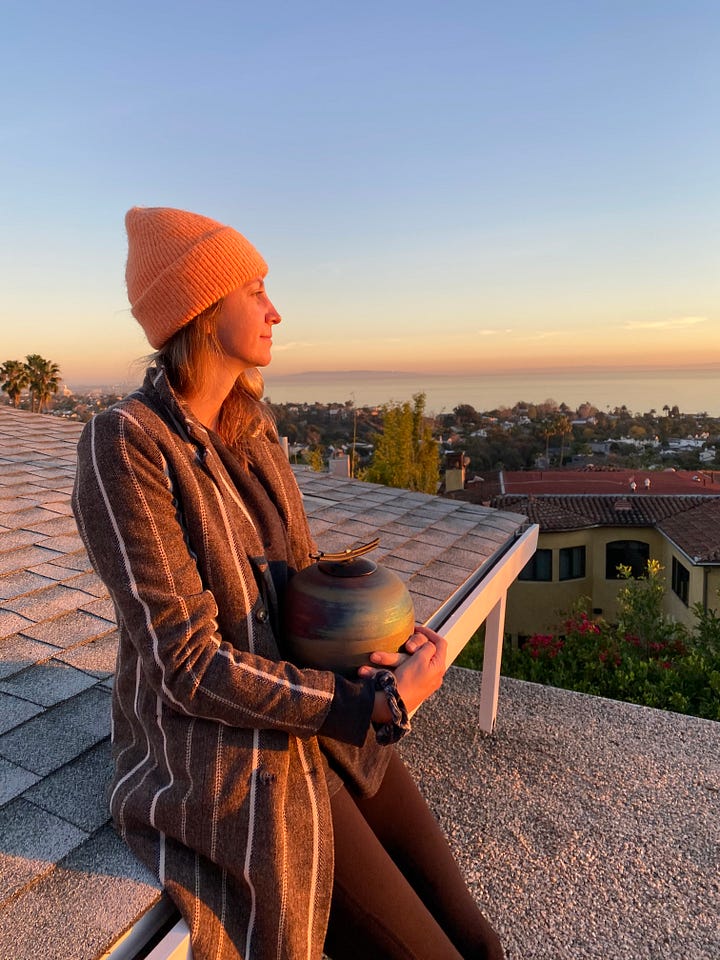

My mom died five years ago to the day that the fire took our house. Most everything she owned is gone. Every small piece of jewelry, every photograph she placed under plastic film in a photo album with a dated note. Her heart and soul were in that house which she lovingly renovated with my dad, her partner of 40 years. She unexpectedly died during a surgery in January 2020, sending shockwaves through our family, then two months later the pandemic started. We crawled out of that mess. I had another baby. And I never made the time to properly go through her stuff. I trusted that it would always be there when I was ready. I wasn’t ready yet. And it’s now gone.

How do we categorize losses of the parts of ourselves that we can never revisit? When my husband and I moved to Los Angeles in 2017, we moved into the house with my parents and our 4-month-old son. When we moved out a year and a half later, we only took the stuff necessary for life with a toddler. Everything I brought with me from 15 years in New York City is gone. Parts of myself that I now struggle to find connection within my sleep-deprived, stressed-out early-40s-with-2-young-kids-and-a-bad-back phase of life. All evidence of myself as an artist went up in flames. My youth burned, something that I have already been grieving as I enter perimenopause. The hard drives of photos, writings, ideas for plays, essays, and creative projects from my 20s in the downtown theater scene, my journals starting as young as 4th grade, books and plays I had carefully marked up and deconstructed inside. One day they were there, adding a familiar weight to my existence. The next, they vanished. I find myself drifting.

My kids might never see videos of me performing at Joe’s Pub in the early 2000s before I was a therapist. I fear I will never reconnect with the passion and immediacy I felt when youth made all things still possible. When life was in clear definition, and I was a political activist artist who lived in full alignment with my ethical values. Before I got gentler with myself and prioritized healing from trauma rather than just living. Before having to think about diapers, summer camps, future college, rising rents, rapists as presidents, the impact of social media on young minds. Before I realized that home ownership might never be available to me. That the environment and our climate future is looking increasingly bleak.

Would I have ever been ready to revisit the boxes stored under the house? I don’t know, but if you had asked me, I certainly was planning on it.

Growing up in the Palisades of the 1980s and 90s, we were no strangers to natural disasters. We’d joke that we had 4 seasons: fire, mudslide, earthquake, and summer. My AYSO soccer team even named ourselves “The Natural Disasters” one year. While I knew of one or two families who were displaced by wildfires, the level of destruction the Palisades and Eaton Fires have left us with today is unprecedented. These aren’t natural disasters, they are climate disasters, and they are showing up in frequency and intensity all over the world. My elementary and middle school, our rec center, our library, the local community theater, the banks, post office, grocery stores, our favorite restaurants, they all have been taken out. Rows and rows of houses were unable to be protected because of nightmarish winds. At this moment I can name more than a dozen families who now have three generations displaced, three generations within a single family who have lost all their belongings, their homes, their memories, their children’s schools and parks, their places of worship, their center.

I remember the Palisades before big developers arrived. A young family on a single fixed income could buy a house in the 1980s and make a dream life there. Pacific Palisades was a beach town between the more famous Malibu and the larger Santa Monica, one that attracted and could accommodate all types of people. It was a predominantly white community, but not all people were wealthy. Celebrities were still kind of novel, and I learned at a young age “not to bother them” because “they are just hoping to live their quiet lives too.” It was seen as an escape from the flashier side of the Los Angeles entertainment industry. As a kid, I took part in the annual 4th of July 5K run/walk and marched in the parade. We painted local business’ windows for the town Halloween Window Painting Contest (and even won once!). I became a theater kid devoted to all things Andrew Lloyd Webber with Theater Palisades Kids and the Adderley School. I was an altar server at Corpus Christi Church, and when we held my mom’s funeral there 22 years after I graduated 8th grade, almost every one of my 31 person elementary school class showed up with their parents. These families helped raise us all, and we continue to be deeply interwoven and connected. We knew our neighbors, so many of them have just lost everything, many of whom would not have been able to buy into the Palisades of recent years. I fear that much of the culture of the community that I grew up in, loved, and that shaped me will disappear due to this disaster.

What was lost feels multilayered and complex. Community loss, family loss, personal loss, financial loss, loss of identity, loss of possibility, loss of history, loss of connection. And yet, I am finding it hard to process these losses in light of how much we still have. When you have had a lot and you lose it all, in many ways you still have a lot.

When my dad evacuated, we joined him at a friend-of-a-friend’s house in the desert. It was an exquisitely beautiful place covered in modern art and wide glass walls looking out onto a pristine golf course. There was a long white lacquered table, and we were generously given the opportunity to come together in a spacious way, to slow down, to cook for each other, and to share stories and laughter. We experienced abundance yet again, even in the moment of such crisis. I’d imagine that few people who were evacuated or lost homes had this experience. Similar to the pandemic, we find ourselves weathering the same storm, but often in vastly different vessels. There will always be someone who has lost more. And yet, yes, we have lost.

The first 24 hours of evacuation contained a lot of hope for me. And damn, hope can be brutal. Checking the fire apps constantly, refreshing the news, looking for notifications, joining groups of strangers on WhatsApp who were instantly connected due to geography or shared desperate hope. A family friend took his motorbike up to the Palisades on Thursday (two days after the fire started) and captured a few photos and a video of our home. I had been praying for a miracle, but we didn’t get one. Nothing was left.

Sitting at the Ace Hotel diner in Palm Springs, I got my first glimpse of photos, unimaginable up to that point, that have now entered our collective consciousness. Images of burned-out sites with one or two beams still standing, a chimney rising in a vast bombed out space gently mirrored by an iconic palm tree in the blue skies. I felt my body start to shake and a sob release. My hands rose to cover my eyes, and I cried uncontrollably in that restaurant, surrounded by many other people who gave me that generous public space for my private grief that I had only previously found crying on the New York subway. It was such a relief having answers. And the pain was acute.

I cried for my mom, gone too young. I cried for a community, for fear of its permanent destruction. I cried for a world that continues to be less and less stable, less equitable, less free. I cried for our earth, for what we are doing to her out of raw, unfettered greed. I cried for myself, for all the parts of me who went up in smoke and live on only in select memories. And I cried for a house that was more than four walls, a rock covered roof, and a killer view. I finally could begin to accept the impossible.

My family is still waiting for the embers to cool so we can go through the ashes. I want to walk the streets that are charred and see it for myself. I have a vision of sprinkling wildflower seeds on the ashes of our home, just as we sprinkled my mom’s ashes off the roof of the house we thought would be in our family for decades. My kids don't remember my mother’s face, but we tell them stories about her. The older I get, as my hair goes gray and lines take permanent residence on my skin, the more her face shines through mine.

When everything gets taken from you, you have choices. Do you continue gripping? Do you let the experience release you in some way? How do you handle the rage, the fear, the envy, the surprising freedom - giddiness! - of surrender? (Cue in Bob Dylan’s nasal croon, “When you have nothing you have nothing to lose.”) Every hour brings some new jolt of feeling, feelings that live in contradiction to each other. It is an exhausting whiplash. In many ways the news coverage and the world have already moved on.

When people ask, I say: We lost everything. But… we have lost everything before. It's all a cycle: grow, live, burn, grieve. It's not an easy cycle, but we delude ourselves to imagine otherwise. And I continue to wonder if like glass being tempered, might we be made stronger through the flames? What we have lost will never be replaced. The grief is deep, and minimizing or glossing over it would be a cruel task. The work instead becomes about expanding ourselves, so that this specific pain someday takes up less in proportion to how big our lives continue to grow.

Absolutely beautiful. Thank you for writing and sharing this. We love y’all

Danielle, I feel so much connection and love when reading this - deeply tainted by sadness, heaviness and grief trying to grasp what you and so many others went through. The way you were able to put it in words is truly magical and very meaningful. The world needs this. And you.